By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

‘Witches’ Review: Elizabeth Sankey Reflects on Postpartum Mental Illness in Veracious Documentary

Alison Foreman

“Being good or bad isn’t a choice a woman gets to make by herself,” filmmaker Elizabeth Sankey narrates in her spellbinding new documentary, “Witches.” It’s an incisive perspective on an age-old cinematic question that’s never had a good enough answer: “Are you a good witch or a bad witch?” as Glinda once asked. As Sankey might see it, the question itself put Dorothy in danger.

Our ever-shifting sense of women’s autonomy resonates in countless contexts, and that’s worth keeping front of mind throughout this feature-length consideration of postpartum mental health and the historic persecution of women. Weaving personal experience and keen anthropological theory into a lush and haunting tapestry of magical portrayals from pop culture, Sankey achieves an intricate archival exposition backed with tremendous feeling. She uses old film footage, insightful interviews from experts and friends, and select theatrical scenes (all silent) shot specifically for the documentary to help underscore the subject’s timelessness.

At Tribeca in 2019, the director, writer, and editor premiered “Romantic Comedy,” a thoughtful consideration of the chick flick that centered Sankey’s personal experience with love and love stories. That project questioned how what its creator saw onscreen in genre staples like “When Harry Met Sally” and “Notting Hill” changed her expectations for a romantic partnership in real life. To support that social science dissection, Sankey drew on the experiences of actors, writers, and other filmmakers.

First comes love, then comes marriage, so naturally, “Witches” pivots to center on Sankey’s next harrowing life milestone: becoming a mother.

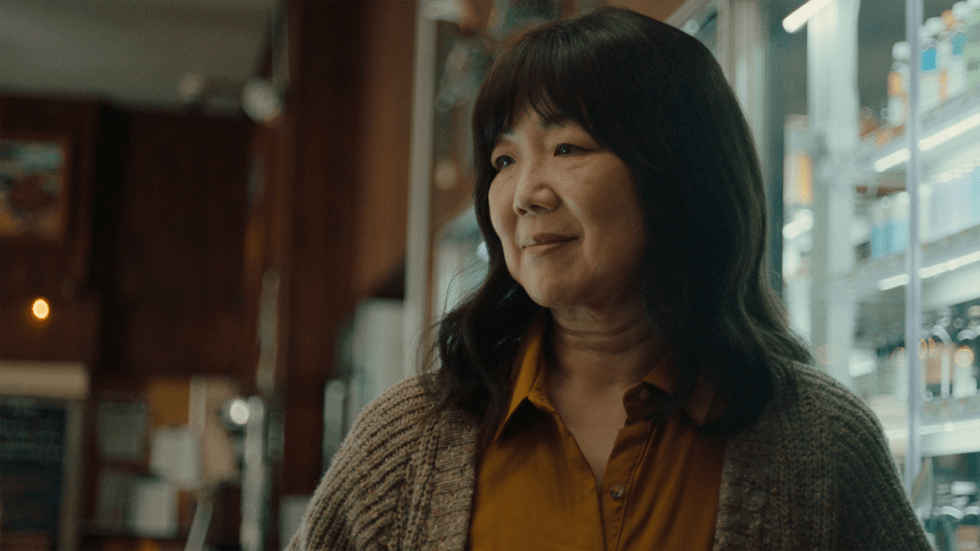

The subject of procreation sees Sankey move away from Hollywood and mostly to her sophomore effort’s benefit. Grappling with extreme feelings of anxiety and depression after giving birth, Sankey and her infant son were admitted to a psychiatric ward when she began to fear for their safety at home. Clips from classic witch movies (think “Practical Magic,” “Suspiria,” “The Craft”) as well as select images depicting motherhood and mental illness (“Tully” and “Girl, Interrupted” make appearances) adorn testimonials from 13 people, including Sankey. The filmmaker leads her de facto coven’s narrative at its start but opens the film up for reflections on numerous troubled pregnancies and their sometimes devastating impacts on young families.

Author Catherine Cho, whose book “Inferno: A Memoir of Motherhood and Madness” details the pure terror of postpartum psychosis, illuminates elements of involuntary hospitalization that Sankey’s more community-based treatment experience does not. Selected images of devils from films like “The Conjuring” are paired with Cho’s disturbing descriptions of the visual and auditory hallucinations she endured for months while her child grew up without her.

In tandem, David Emson (the only male voice in the documentary) recounts the highly publicized loss of his wife and daughter in brutal detail. An accomplished doctor, his wife Daksha Emson died by suicide after murdering her infant daughter Freya in 2001, supposedly believing she was saving the baby from an unseen evil. Her widow speaks graciously about his late wife and her unique role in the postpartum conversation as both a sufferer and healthcare professional. Still, Sankey acknowledges Daksha as a polarizing figure whose reputation as a woman (or is it witch?) is settled as neither villain nor victim.

Other fellow survivors, many from the online peer group Motherly Love (which Sankey credits with saving her life), appear for interviews alongside healthcare professionals and historians. Collectively, these voices connect folklore and the real witch trials of yesteryear from across North America and Europe with the well-documented denial of women’s basic healthcare needs for centuries. In the end, “Witches” answers the good witch/bad witch dichotomy with its own question: Is it possible the women — whom humanity burned at the stake for visions, hysteria, and an unspeakable pain innate to their life’s supposed purpose — were in fact facing extreme cases of premodern baby blues?

As a matter of film celebration, Sankey’s title is perhaps misleading. Unlike “Romantic Comedy,” this documentary barely scratches the surface of witchy cinema, an educational arena with beguiling artistic depths that could provide the basis for a handful of film school courses or a multi-part docuseries. Still, “Witches” bottles the most important themes routinely explored through those motifs, existing as the ideal nonfiction companion to enchanting works like Apple TV+’s “The Changeling” or Focus Features’ “You Won’t Be Alone.” With a generous scope and ease of tone, Sankey never fails to let her most vulnerable material breathe even as the subject’s enormity threatens to suffocate.

Grade: B+

A Mubi release, “Witches” premiered at the 2024 Tribeca Festival.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.